WELCOME TO THE UNIDO MONTREAL PROTOCOL NEWSLETTER

In this issue, we are diving deep into the practical aspects of implementing the Kigali Amendment; recognising that policy measures and approaches may vary from country to country, depending on the national needs and circumstances. Read on to learn about possible control measures from two unique perspectives: Tunisia’s experience in establishing a hydrofluorocarbons (HFC) licensing system and the challenges and lessons learned in Austria on initiating the HFC phase-down.

We are also pleased to share some insights on UNIDO’s response to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) global crisis: how we have adapted our implementation modalities and the innovative solutions we have found together with our Member States. Finally, for some lighter entertainment, we welcome you to solve our crossword puzzle and test your knowledge of the Montreal Protocol terminology.

Thank you to all the readers who have reached out to us. We welcome additional feedback and questions by means of the contact form at the bottom of this page. We will happily respond to your technical questions in the “Ask UNIDO” section in one of the next issues.

Happy reading!

Your UNIDO Montreal Protocol Division Team

ASK UNIDO

Associate Industrial Development Officer at UNIDO, explains the effects of COVID-19 on the manufacturing sector and how UNIDO is working to mitigate this impact.

INTERVIEW

National Ozone Officer Tunisia and UNIDO Project Coordinator, on Tunisia’s experience in developing a HFC licensing system.

FEATURE ARTICLE

Expert at Environment Agency Austria, shares her experience on the challenges and lessons learned in Austria for the HFC phase down.

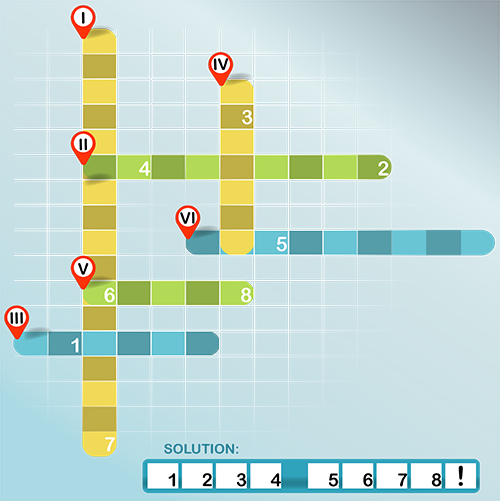

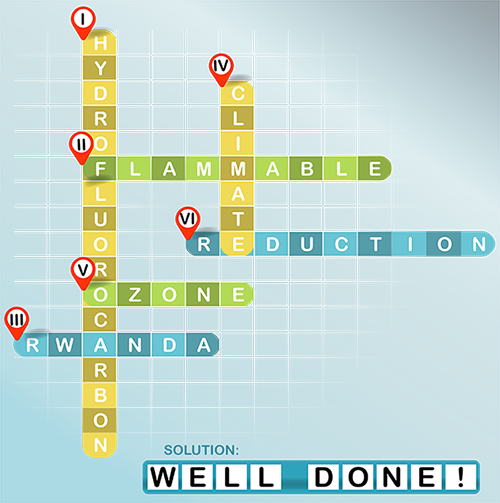

CROSSWORD

- I. Substance that contributes to global warming, with up to thousands of times the warming potential of CO2.

- II. Characteristic that R32 and hydrocarbons have in common (adjective).

- III. Country in which the Kigali Amendment was adopted.

- IV. Global warming causes change in this long-term average of the earth´s weather.

- V. Its layer protects us from harmful UV radiation reaching the Earth´s surface.

- VI. UNIDO helps countries to meet these targets of the Montreal Protocol/Opposite of increase.

NOTICE BOARD

Notes

-

Social Media

UNIDO’s Montreal Protocol Division commemorates International Women’s Day and calls for action on gender equality.

Notes

-

Events

UNIDO’s Montreal Protocol Division invites you to take part in our upcoming virtual events.

Notes

-

Spotlight

The NOU of Burkina Faso releases a fun and informational video on “How to ensure high-quality refrigerant (French)".

Correct! the answer is: B

Wrong, the answer is: B

- The Paris Agreement was opened for signature on 22 April 2016 (Earth Day) and went into effect on 4 November 2016.

- The aim of the Paris Agreement is to: hold the global average temperature well below 2 °C above the pre-industrial level and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above the pre-industrial levels.

- The Kigali Amendment was agreed upon in 2016 and entered into force in 2019. The Kigali Amendment builds on the historic legacy of the Montreal Protocol agreed in 1987.

- The agreement will see an 85% phase-down in developed countries by 2036, an 80% phase-down by 2045 in most developing countries including China, and the remaining developing countries reaching an 85% phase-down by 2047.

- The Paris Agreement was opened for signature on 22 April 2016 (Earth Day) and went into effect on 4 November 2016

- The aim of the Paris Agreement is to: hold the global average temperature well below 2 °C above the pre-industrial level and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above the pre-industrial levels.

- The Kigali Amendment was agreed upon in 2016 and entered into force in 2019. The Kigali Amendment builds on the historic legacy of the Montreal Protocol agreed in 1987.

- The agreement will see an 85% phase-down in developed countries by 2036, an 80% phase-down by 2045 in most developing countries including China, and the remaining developing countries reaching an 85% phase-down by 2047.

ASK UNIDO

You Ask, We Answer!

Yunrui Zhou, Associate Industrial Development Officer at UNIDO, explains the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on the manufacturing sector and how UNIDO is working to mitigate this impact in developing countries.

How is UNIDO helping to support countries respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and lessen its impact?

Under the leadership of the Director General LI Yong, UNIDO published its framework “Responding to the crisis: building a better future[1]” in May 2020. The framework outlines three integrated packages to support Member States with comprehensive socioeconomic recovery approaches, namely: (1) Prepare and Contain, (2) Respond and Adapt, and (3) Recover and Transform. More information about these three approaches can be found at the following link:

https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/files/2020-05/UNIDO_COVID19_External_Position_Paper.pdf

In early February 2020, in addition to the implementation of ongoing and planned programmes and projects, UNIDO initiated specific activities to respond to the challenges of the crisis as a matter of urgency. Particularly at the early stages of the crisis, it was important to provide information on the consequences of the pandemic and measures to mitigate its impact. The Department of Policy Research and Statistics has published a series of analyses, opinion pieces and articles on the impact of COVID-19 and its mitigation.

Drawing on longstanding experience with industrial upgrading and modernization of enterprises and institutions, UNIDO launched the “COVID-19 Industrial Recovery Programme”. The publication on responding to the COVID-19 crisis: Pathway to Business Continuity and Recovery provides guidance to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) on how to respond to the crisis and build a better future.

How has UNIDO adapted its work under the current circumstances? What are some things you and your colleagues are doing differently?

Following guidance provided by host country authorities, UNIDO required all personnel to work from home during the period 16 March- 18 May 2020. At present (November 2020), our host country Austria has once again entered a second lockdown, meaning that all UNIDO personnel are once again working from home until further notice. Additionally, all official travel and physical meetings are restricted to essential and critical until further notice. In addition, UNIDO has substantially reduced in-person meetings (max. 3-4 people, with a distance of 1 meter between participants), and almost all communication is now virtual.

Due to travel restrictions and the closures of borders, in addition to other containment measures around the globe, UNIDO has had to adapt its implementation modalities and find innovative solutions to continue its work. One example is the increase of online webinars as opposed to in-person events. Such webinars – including a recent series on HFC licensing practices – allow us to increase the exchange of good practices between regions and bring together a wider scope of participants, all while reducing our carbon footprint. Another example is an increased recruitment of local experts to support the implementation of projects. UNIDO takes the utmost care to ensure national experts abide by national COVID-19 measures during their assignment.

What are some of the main challenges that industries are facing now during the pandemic? How is UNIDO helping them?

The COVID-19 crisis started as, and remains primarily, a public health emergency with widespread loss of life and human suffering. The measures required to contain the spread of the virus turned the pandemic into a severe economic crisis, with many additional socio-economic consequences[2].

The manufacturing industry has experienced challenges on both the demand and supply sides. A combination of shop closures, unemployment and lower income, together with other uncertainties on the consumer side, resulted in lower spending and a drop in demand for goods, followed by the considerable decline in commercial activity. Even in countries in which containment measures were less stringent, the sharp fall in external demand affected the economy. On the supply side, with factories either closed or operating well below capacity, output dropped. Production is further hampered by the lack of intermediate supplies, which in turn disrupts cross-border production networks and global value chains, compounding the effects of the fall in demand[3].

The COVID-19 crisis is directly affecting the majority of the world’s workforce and unemployment rates are skyrocketing across the globe. The collapse of firms in the manufacturing sector, with often more extensive linkages in value chains than other sectors, could multiply the negative impact on people. Unemployment effects are felt disproportionately across industries, with the highest impact on wholesale and retail trade, and the manufacturing industries, where lower-skilled and lower-paid workers, often women, are particularly affected. Micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, self-employed persons, daily wage earners, part-time workers and those insufficiently covered by formal working arrangements are being hit particularly hard by the crisis.

Given that the manufacturing sector, industry-related services and their workforce are directly affected by the crisis and will constitute one of the most important elements of the recovery period, the mandate of UNIDO has undeniably become more important than ever. As the specialised UN agency for industrial development, UNIDO is at the forefront of efforts to build a more resilient, greener and circular global economy.

Take the implementation of the stage II of the hydrochlorofluorocarbons phase-out management plan (HPMP) for Oman as an example. The activities delivered as part of stage II of the HPMP, contribute fully to the mitigation of the economic effects of COVID-19 and drive rapid recovery. Stage II of the HPMP includes, in particular, activities to ensure that refrigeration technicians are trained on the latest technologies and skills, protecting them against labour market risks. Further to this, the transition to alternative technologies will help Oman reduce emissions of ozone-depleting substances and CO2 while also generating green jobs essential to the economic recovery of the country. In addition, since almost all activities under the HPMP are to address needs of the refrigeration service sector, it is highly anticipated that UNIDO’s interventions will contribute to the efforts for building a better future, since the refrigeration and air-conditioning (RAC) sector is an essential integrated part of all economic activities in the country. Any improvement in the RAC sector will have positive impacts in all sectors. Under the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, with joint efforts of all stakeholders, UNIDO has thus far contributed to the phase-out of over one third of ozone-depleting substances from the developing world.

[1] Responding to the crisis: building a better future, May 2020, UNIDO

[2] UNIDO’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, IDB.48/11

[3] Industrial development cooperation, United Nations General Assembly A/75/158

INTERVIEW

Interview with Youssef & Andrés

Youssef Hammami, National Ozone Officer Tunisia and Andrés Celave, UNIDO Project Coordinator, on Tunisia’s experience in developing a HFC licensing system.

Tunisia has taken early action to ratify the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol and enforce control measures on HFCs. When did this process begin and how far along have you come?

The process started in 2017 when Tunisia was granted by the Montreal Protocol Multilateral Fund and the Government of Italy the necessary funds for undertaking enabling activities for the ratification and early implementation of the Kigali Amendment.

Today, the process is almost finalized. This October 2020, the Tunisian Parliament ratified the amendment and now we are working on depositing the instrument of ratification with the United Nations Secretary-General in New York. We updated the tariff codes to better identify HFCs imported to the country and we are currently working on the approval of the legal text that will officially integrate these substances into our licensing system. In addition, we have produced several reports that study the implications of the Kigali Amendment in Tunisia from different approaches:

- Legal and institutional framework,

- Market trends and technological alternatives,

- Refrigeration and air conditioning sector,

- Codes and standards, and

- Capacities of the servicing sector.

A summary report has also been produced which will serve as the main reference for developing the future national strategy for HFC phase-down in our country. Finally, information events have been delivered in different regions of Tunisia to raise awareness on this crucial subject.

It is also important to highlight the role of partnerships in the process. We have greatly strengthened the collaboration between Tunisian and international experts as well as partners, including UNIDO; such partnerships provide a solid base needed to better implement the provisions of the Kigali Amendment in the coming years.

How did you undertake the preparation of the legal text and the updating of the tariff codes for the HFC licensing system?

The legal text for including HFCs among controlled substances under the licensing system was undertaken by the Ozone Unit with the support of a national legal expert. The text tackles the import of those substances indicated in Annex F of the Montreal Protocol, which were introduced through the Kigali Amendment. But it also extends the licensing system to the export, management and handling of HFCs, as well as the management of HFC-based equipment. The text has to be approved by the Tunisian Ministry of Environment for its entry into force.

However, the HFC licensing system would not be operational without the appropriate tariff codes for precise identification of those substances imported or exported to and from the country. Therefore, we undertook efforts to update those tariff codes in 2018. For this, the Ozone Unit worked in collaboration with the Tunisian Customs Office, in particular with the Direction of the Customs Nomenclature, to assign specific tariff codes to the most common HFCs imported into our country (HFC-134a, R-404A, R-410A, HFC-32), following the international Harmonized System nomenclature. These new codes (which you can see in the table below), in combination with the updated licensing system, will help us to monitor all the HFCs shipments reaching the country.

What are the necessary actions to inform importers and other stakeholders on the licensing system and the tariff codes in place?

Proper communication is key for the effective implementation of new tariff codes and the upcoming licensing system. In this respect, we directly contacted all importers in 2018 to inform them on the new codes, and we transmitted this information to the General Directorate of Foreign Trade within the Ministry of Commerce. Additionally, other communication channels have been used which include training and information sessions for importers, customs officers and other stakeholders, different websites and social media platforms, and last but not least, the electronic licensing system, which is a digital platform for import authorization.

How did you manage the transition from a traditional (paper) licensing system to the current electronic system? What are the recent improvements made to the electronic system under the enabling activities project?

This transition took place in 2017 when the Ozone Unit decided to make use of the electronic customs platform called Tunisie Trade Net (TTN). The platform had been created in 2006 for the digitization of all administrative procedures linked to the trade of all type of products, including ODS and HFCs. All that was required in this case was to add the necessary functions for the licensing of those imports. This way, the Ozone Unit has access to information about every shipment of ODS or HFCs and can authorize or reject their final import into the country through the TTN platform.

The recent improvements are mainly focused on two aspects:

- Allowing access to the platform from any computer. So far, this was only possible from the Ozone Unit office.

- Develop statistics about imports. We will be able to analyse the total amount of imports per substance or per importer, among other criteria.

These improvements will facilitate our monitoring activities for better control of those substances imported into the country, better communication with importers and an increased transparency across the entire licensing system.

FEATURE ARTICLE

HFC phase-down: challenges and lessons learned in Austria

Maria Purzner, Expert at Environment Agency Austria, shares her experience on the challenges and lessons learned in Austria for the HFC phase down.

Introduction to HFC legislation in Austria

F-gas regulations in Austria represent a long and ambitious, but rewarding, process in policymaking. F-gases have been subject to control since the early 2000s: in 2002, the Austrian government issued the first Ordinance of the Federal Minister for Agriculture and Forestry, Environment and Water Management on bans and restrictions on HFCs, perfluorocarbons (PFCs), and sulphur hexafluoride (SF6). Whilst PFC and SF6 usage control worked well, and led to immediate measures by industry, control of the use of HFCs represented more of a challenge. HFC use was controlled by allowing a maximum load for different types of equipment – with room for exceptions – and a requirement on reporting the uses of HFCs, which was more challenging to control, given the number of small enterprises working in the field (around 1,200 in a country with a population of 8 million). Whilst the use of PFCs, as well as SF6, decreased over the years, HFC usage continued to increase.

In 2006, the first version of the European Union (EU) regulation (EU Reg. 842/2006) introduced further controls on the use of HFCs – it should be noted that EU regulations are directly applicable in the national law of member states. The main provision outlined that in order to avoid emissions of HFCs, refrigerants should be handled only by certified, i.e. trained maintenance and service technicians, who understand the importance of the containment of HFCs during transport, storage, application and decommissioning, avoiding leakage (through leakage checks) and the careful handling of refrigerants. Imports and the production of HFCs were regulated through obtaining a quota, which allowed for monitoring of the amounts of HFCs placed on the EU market.

Another important issue was the ban on non-refillable containers for refrigerants. This ban led to a more “local” approach in retailing on the one hand, as importing refrigerants in refillable cylinders meant having to send them back empty, which increased shipping costs. However, on the other hand, avoiding non-refillable cylinders being disposed of as scrap metal meant that excess refrigerants were either destroyed or recycled instead of emitted.

In 2014, the current version of the EU regulation (EU Reg. 517/2014) was issued, which came with significant additions to the 2006 version. The provisions for certifications were extended in a way that refrigerants could only be traded between certified companies or personnel. This led to a surge of issued certificates: in 2014, approximately one fifth of all 1,250 companies (the majority being 1-2 person companies) were certified, in 2019, approximately 99% of all known companies were certified.

Challenges in the quota system

The EU then had to tackle the challenge of managing quotas. Several trading companies, as well as end users (research institutes, equipment producers) tried to obtain a quota; however, as the grandfathering principle is applied in Austria, these companies were unable to obtain the full quota they wanted. The grandfathering principle means that companies that had a quota before 2015 are to be treated with priority, and the remaining amounts to be split between newcomers. The existence of quotas has led to a market of quota trading, which was curbed by illegal imports of HFCs into the common market.

Unforeseen vs expected market developments

The most important novelty of the 2014 regulation was the planned phase-down on the total of HFCs used in the European market: in 2015, 100% of HFCs were allowed (based on the baseline of 2008-2012 in CO2 equivalents), in 2016-2018, 93%, and in 2019, 63% of the baseline. This led to several unexpected situations in Austria: Industry representatives in 2015 were optimistic that the phase-down would pose no problem and that the industry was ready.

However, high prices of new (and flammable) hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) or HFO-HFC blends had not been taken into account, as well as the price increase of existing HFCs, especially those with a high Global Warming Potential (GWP) such as R410A. This resulted in industry representatives trying to obtain an exemption for the refrigeration, air conditioning and heat pump sector from the regulation, which was not approved by the Ministry in charge. Their argument was that a shortage of HFCs could lead to dangerous situations, for example hospitals running out of refrigerants and that the increase in price of refrigerants was a competitive disadvantage.

However, the total amount of refrigerants placed on the market is not attributed to individual EU member states, but trade between member states is possible. Some member states were more advanced in their phase-down measures, which meant that there was no shortage of refrigerants on the common market. Refrigerants had simply become more expensive, which was the expected result and incentive for the industry to think ahead and apply alternatives.

Overall, the experience from Austria indicates that the phase-down hit smaller companies harder than bigger ones, simply because they had not taken the regulation seriously, or had not been aware of changes.

Regularly updated training is the key to success

Another challenge to be overcome in Austria was that of training necessary due to the changed market. Previously, the use of flammable or toxic refrigerants had not been an adequate part of most training curricula: trainees or technicians trying to specialize in non-halogenated (natural) refrigerants, such as hydrocarbons, ammonia or CO2 faced only a small choice of positions, as well as training programmes. This led to several initiatives looking at increasing possibilities for training programmes for zero- or low GWP refrigerant alternatives, as well as some companies that understood the signs of the time and profited from the provisions of the F-gas regulation.

As for training on the safe use of alternative refrigerants, they need to be ongoing, and an emphasis needs to be put on all aspects of energy efficient cooling, i.e. maintenance, leakage control, choice of refrigerant and planning of equipment.

Remaining challenges and new opportunities

What remains unsolved to date is an intrusion of illegally imported amounts of refrigerants into the market, particularly R134a and R410a. This was due to the wording of the regulation and the fact that only the initial placing of banned refrigerants onto the EU market was punishable. “Legally” obtained (i.e. purchased) amounts could not be fined, leading to a situation where a possible fine was lower than the profit made with even small amounts being imported in private cars. Several EU member states are trying to apply additional laws to be able to fine whoever acquires illegally imported refrigerants.

Lastly, Austria, like many other European countries, experiences heat waves during summer, which led to a surge in the sales of energy inefficient, small equipment, such as mobile room air conditioners and mono-split equipment. Solutions are necessary and need preparation, taking into account passive measures, including shading and ventilation, and active measures, such as district cooling and the use of anergy networks, whilst preserving facades in historical city centres.

A lot remains to be done, but the good progress already made and the big impact these measures have on our environment keeps us motivated.

CONTACT US

Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to receive a quarterly email with updates and new content!

Disclaimer

The information presented in this newsletter does not necessarily reflect the views of UNIDO. Links to external websites are included solely to provide additional information and do not imply any official endorsement of the opinions, ideas, data, or products presented.

© 2020 UNIDO Montreal Protocol