Welcome to the UNIDO Montreal Protocol Newsletter

In our 4th edition, UNIDO’s Montreal Protocol team would like to take you on a trip around the world. Our first stop will be South Africa where we will discuss the environmental and business aspects for the recovery, recycling and reclamation of refrigerants.

Next, we travel to Mexico to listen to the insights from the National Ozone Unit’s two-day training on Gender Mainstreaming and why this could be beneficial for your country. Our trip’s finale will be in Burkina Faso, where we will hear about the country’s experience and lessons learned from their Enabling Activities project.

On the way, we invite you to discover more destinations in our UNIDO country quiz, event announcements and videos in the notice board.

Finally, we welcome you to reach out to our team by submitting your questions to the “Ask UNIDO” section or any suggestions for the newsletter via the form at the bottom of the page.

Happy reading!

Your UNIDO Montreal Protocol Division Team

ASK UNIDO

Consultant for Montreal Protocol project implementation, answers the question “Reclaiming refrigerants in the context of climate change – why is it important and how does UNIDO provide support?”

INTERVIEW

Institutional Strengthening Coordinator in Mexico, Environment and Natural Resources Ministry (SEMARNAT) shares her experience on the impact of Gender Mainstreaming in Mexico.

FEATURE ARTICLE

National Ozone Officer of Burkina Faso and International Consultant on the Enabling Activities project for the HFC phase-down in Burkina Faso.

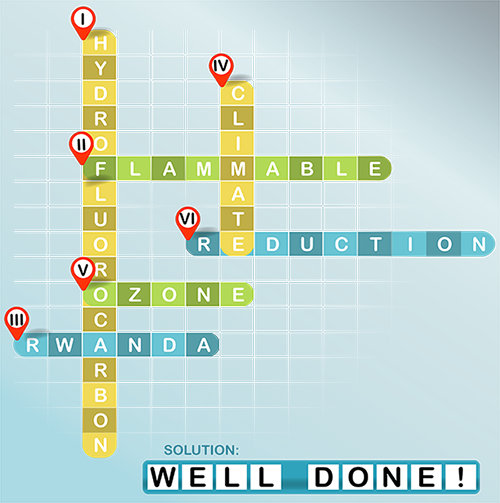

QUIZ - Guess the country and click on the card to see the answer.

NOTICE BOARD

Notes

-

Social Media

UNIDO’s Montreal Protocol Division commemorates International Women’s Day and calls for action on gender equality.

Notes

-

Events

UNIDO’s Montreal Protocol Division invites you to take part in our upcoming virtual events.

Notes

-

Spotlight

The NOU of Burkina Faso releases a fun and informational video on “How to ensure high-quality refrigerant (French)".

ASK UNIDO

You Ask, We Answer!

Irma Lizde, Consultant for Montreal Protocol project implementation, answers the question “Reclaiming refrigerants in the context of climate change – why is it important and how does UNIDO provide support?”

(5min reading time)

What is RRR – recovery, recycling and reclamation?

In the context of refrigerants, it is worth noting that recovery, recycling and reclamation are three very distinct things. It is important to point this out as reclaimed refrigerants are often mistakenly referred to as recycled; however, recycling is, simply put, cleaning, i.e. removing dirt and debris. Reclamation, on the other hand, is a more intense and elaborate, chemical process which additionally analyses and filters specific contaminants and cleans the refrigerant to an extent where the quality is ‘restored’ to its original state and the refrigerant meets the required purity specified in AHRI Standard 700. The official definition given by our main donor, the Multilateral Fund for the Implementation of the Montreal Protocol, details this further as “the re-processing and upgrading of a recovered, controlled substance through such mechanisms as filtering, drying, distillation and chemical treatment in order to restore the substance to a specified standard of performance’.[1] Once the refrigerant is recovered, it is placed into a refillable cylinder so as to prevent leaking or venting into the atmosphere.

Why is RRR so important?

This question can be answered from two different perspectives depending on what you perceive as more important: the environmental or the business aspect (although these are arguably intertwined). Refrigerants play vital, innumerable roles in our everyday lives. This is even more evident in the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic: we are continually learning about the temperatures some of the vaccines have to be kept at and the crucial role refrigerants and cold chains play in this regard. For example, one of the first vaccines that became available, Pfizer-BioNTech, needs to be kept at the very low temperature of -70°C – a temperature colder than winter time in Antarctica. To achieve such low temperatures within refrigerators and air-conditioners, refrigerants are essential.

While some of the most popular refrigerants (hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)) are recognised as potent greenhouse gases which contribute to global warming, and as such, are in the process of being phased-out and phased-down, they are still all too regularly vented into the atmosphere.

The importance of RRR from an environmental perspective is clear and definitive – as is the science behind it. Greenhouse gas emissions have increased 1.5 per cent annually over the past decade, and without a unified and concerted approach to tackling climate change, our planet is heading towards a warming of 3.2 degrees in less than 100 years’ time which would have disastrous consequences.[2] Unfortunately, this is particularly true for countries that have in reality contributed the least to climate change and are equally least equipped to handle the aftermath. CFCs, HCFCs and HFCs have contributed towards this blanket of gases surrounding our planet which has led to global warming. To put their impact into perspective, one residential air-conditioner running on R410A would have a direct CO2emission of six tons during its lifetime, the equivalent of travelling 60,000km by car. Therefore, prohibiting the venting of these gases, while encouraging their recovery and reclamation in the short-term, as well as the uptake of environmentally friendly alternatives in the long-term, is key.

From a business perspective, reclamation also makes sense. For example, as supplies of refrigerant R22, or other high global warming potential (GWP) refrigerants such as R404A, will continue to decrease globally, companies can sell on reclaimed refrigerants for a profit. Additionally, through reclamation the lifetime of products can be extended as we will be able to service them when, for example, virgin R22 refrigerant is banned.

What are the barriers faced by Article 5 countries in implementing RRR schemesand how does UNIDO provide support?

While hopefully demonstrating that RRR is both environmentally friendly and fiscally rewarding, in practise setting up reclamation facility centres and fully eradicating the practise of venting refrigerants may be perceived as challenging. Legislation and fines are important in this respect as well as the right incentives, but re-training technicians not to vent and equipping them with the necessary good service practices on how to handle alternatives is also imperative. Companies which have decided to operate RRR reclamation schemes, either through their own endeavours or as a beneficiary of procured equipment, may face their own business challenges too. One particular barrier is infrastructure, namely ensuring that refrigerants are recovered by technicians as well as motivating them to transport recovered quantities to reclamation centres. The latter is a challenge from the perspective of reclamation centres in their ability to obtain a base stock, i.e. convince enough customers that this is a viable business model and that their refrigerants can be reclaimed, reused, and re-purchased at an attractive price and have the same quality as more expensive virgin refrigerants sold on the market. To a company, operating such schemes can seem challenging – both in terms of costs for procuring reclamation equipment and the time needed to recover, as well as the know-how of those operating such equipment. This is where UNIDO can provide support.

One of the prime objectives of the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer is to facilitate the smooth and sustainable transition from ODS-based technologies to non-ODS without creating local market distortions or an increase in social costs as a result of consumers bearing the costs of the phase-out.[3] Implementing agencies, like UNIDO, can support Article 5 countries through a number of means which include but are not limited to: assistance in the procurement of reclamation equipment for the setting up of reclamation centres, training staff on how to soundly operate the equipment, and teaching technicians how to handle alternatives and adopt good, sustainable service practises.

In terms of the procurement of RRR equipment and training reclamation centre personnel on how to operate it, in 2018 I had the opportunity to help facilitate and take part in a UNIDO-funded reclamation equipment training in Durban, South Africa. As part of the HCFC phase-out management plan (HPMP) Stage I for South Africa, four beneficiaries each received a mobile reclaim unit together with recovery cylinders, hand-held recovery units, gas analysers and vacuum pumps, among other items needed to operate a reclamation centre. Beneficiary representatives were taught how to operate the equipment they had been allocated, and participated in discussions on how to set up the centres and make them fully operational. Similarly, as part of the same project, UNIDO produced a video on how to operate the machinery which others may find useful:

Video: HCFC phase out in South Africa Training video on how to operate a refrigerant reclaim machine

Furthermore, under the HPMP Stage I for South Africa, the same beneficiaries were also invited to take part in study tours, most recently to Dubai to visit a fully functioning reclamation centre and learn of best practises from their international peers. During the current pandemic, while such study tours are currently on hold, UNIDO continues to encourage and facilitate information exchange between countries, more of which you can learn about in the rest of this newsletter.

[1] MLF Decision IV/24: Recovery, reclamation and recycling of controlled substances

[2] UNEP Emissions Gap Report

[3] UNIDO guidelines on “Preparing for HCFC phase-out”

INTERVIEW

Interview with Sofia Urbina

Institutional Strengthening Coordinator in Mexico, Environment and Natural Resources Ministry (SEMARNAT) shares her experience on the impact of Gender Mainstreaming in Mexico.

(4min reading time)

In December 2020, the National Ozone Unit of Mexico successfully took part in a two-day training organized by UNIDO on: Basic Concepts and Introduction to Gender Mainstreaming. Why was it important for you to organize this training and how did you approach UNIDO?

Women’s empowerment is essential to expand economic growth and promote social development. The full participation of women in labor forces would add percentage points to most national growth rates – double digits in many cases.

Promoting gender mainstreaming is an important aspect of the United Nations’ work and is reflected in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls but is also integral to all dimensions of inclusive and sustainable development. In short, all the SDGs depend on the achievement of Goal 5.

While more women have entered political positions in recent years, including using special quotas, they still hold a mere 23.7 per cent of parliamentary seats, far short of gender parity. The situation is not much better in the private sector, where women globally occupy less than a third of senior and middle management positions.

That is why it is especially important to promote gender mainstreaming through Montreal Protocol activities. In this sense, the financial mechanism of the Montreal Protocol (the Multilateral Fund) has been seeking more systematic ways to mainstream gender in the project lifecycle. Four main aspects concerning the way gender differences are reflected in the Montreal Protocol have been identified: the effects of exposure to ozone depleting substances; the decision-making process; the capacity building opportunities; and the working environment.

For the Multilateral Fund, institutional strengthening projects could consider the following indicators: the recruitment of gender experts, the number of gender-specific content disseminated, the number of events focusing on gender, the number of women and men that receive/access information, and the percentage of women present and presenting at training workshops.

In this context, the National Ozone Unit of Mexico requested support from UNIDO’s Office for Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women to organize a gender training. This office was responsible for preparing the course, with the support of UNIDO’s Montreal Protocol Division, tailoring it the case of Mexico and participating in two training sessions.

How was it organized?

The training was organized through the collaboration of the National Ozone Unit of Mexico, UNIDO’s Office for Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women, UNIDO’s Montreal Protocol Division and the support of the Environment and Natural Resources Ministry (SEMARNAT). Communication and exchange of information between participants was particularly important.

The goal of the training was to promote gender mainstreaming and contribute to women’s empowerment and the achievement of gender equality in Montreal Protocol projects.

What are the key takeaways for you and your team? Do you think this kind of training should be organized on a regular basis?

It was important to recognize that there is a long way to go to realize the mainstreaming of the gender approach in Montreal Protocol projects. So, without a doubt, this type of training should be organized regularly.

Training should focus on key aspects of how gender differences are reflected in the Montreal Protocol, for example:

- Gender differentiated effects of exposure to ozone-depleting substances.

- Gender and decision-making.

- Opportunity for capacity building.

- Working environment in industries involved in substance disposal projects controlled by the Montreal Protocol.

- Use of inclusive language.

What do you think are the next steps to move forward?

The National Ozone Unit of Mexico must implement actions to incorporate a policy on gender, taking into consideration SDG 5 and the gender policy adopted at the 84th Meeting of the Executive Committee of the Multilateral Fund for the Implementation of the Montreal Protocol, in December 2019.

For the above, some recommendations are:

- Develop tools to facilitate the process of mainstreaming the gender perspective into the activities of the Montreal Protocol.

- Consider and address gender issues and approaches systematically in all projects prepared to phase out controlled substances at all stages of the project cycle.

- Provide training to facilitate gender mainstreaming.

- Support greater collaboration and participation of gender advisors and gender focal points in project design and execution.

FEATURE ARTICLE

Lessons Learned from the Enabling Activities: the Burkina Faso Experience

Samuel Paré, National Ozone Officer in the Ministry of Environment and Economy of Burkina Faso and Bassam Elassaad, International Consultant for UNIDO write about the recently finalized implementation of the Enabling Activities for the HFC phase-down in the West African country.

(15min reading time)

In the first days of the New Year, the National Ozone Unit (NOU) of the Ministry of Environment, Green Economy, and Climate Change of Burkina Faso was busy preparing the final report on Enabling Activities for HFC phase-down implementation in the country. This important work was being assisted by national and international consultants and UNIDO, who provided support every step of the way. Looking back, the team has a lot to be proud of. First, Burkina Faso was one of the early ratifiers of the Kigali Amendment, having done so in July 2018. Second, the Enabling Activities project was used as a platform for national communication and stakeholder consultations on institutional arrangements, the review of licensing systems and data reporting of HFC consumption. Finally, the team identified and conceptualized elements for a national strategy that will facilitate the HFC phase-down.

During project implementation, the NOU constantly had one question in mind – what the current situation is, and what changes need to happen for the country to successfully phase-down HFCs. The consultants worked in close collaboration with the NOU team in a methodological manner to tackle those issues. Periodic conference calls were set-up to gauge and calibrate the progress and get input from the NOU team. Some face-to-face events were inadvertently curtailed by the restrictions imposed by COVID-19; however, measures were taken to ensure that the exchange of information is adequate to provide an alternative route to those events.

Factors of Success

Two factors contributed to the success of the project: a knowledgeable and energetic national team supported by an international consultancy and a dedicated UNIDO staff, and the central role that Burkina Faso plays in the regional economic community, which enabled discussions on a regional rather than just national level.

The national team included, apart from the NOU staff, an RACHP consultant who has been involved in various projects related to the Montreal Protocol, and a customs and regulations consultant with intimate knowledge of the local and regional landscape. The two consultants participated in all virtual meetings, which were running on a biweekly basis for a period of over six months. Their input was based on research with further consulting other stakeholders to present a holistic picture of the different issues. An example of the output is four recommendations that the team made to institutionalize and harmonize technicians’ training and facilitate certification schemes, especially in the informal sector.

The regional factor played a big role in the preparation and the discussions although the outcome did not yield immediate results. Burkina Faso is a member of ECOWAS, the Economic Community of West African States, and of UEMOA, the West African Monetary Union that within ECOWAS promotes economic integration among countries that share the CFA franc as a common currency. Both communities have regulation on regional levels, especially for labelling and energy efficiency, which means that entities in member states must comply with the national regulations as well as the two regional ones. To come up with recommendations on some of the issues, the enabling activities team had to navigate the complex matrix of regulations and directives issued on the three levels.

Recommendations for Service

Burkina Faso is a low volume consuming (LVC) country with its entire consumption in the servicing sector. The sector comprises close to two thousand formal and informal technicians. Technicians working in the formal sub-sector are dedicated full time owners of medium workshops or employees of larger ones, while those in the informal sector are either seasonal or working without registration. Naturally, the skill level and the training capabilities of the two sub-sectors are different: the formal sub-sector has qualified technicians with earned diplomas and certificates that also received extra training, while those in the informal sub-sector acquired their skills through limited time apprenticeships with technicians that are more qualified.

The Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol brought in an added urgency for ensuring that the skill levels across the two sectors improve to the point where they can handle the challenges posed by the alternative refrigerants in terms of pressure, flammability, or the need to maintain energy efficiency. Technicians having to handle hydrocarbon need to apply the proper security measures for their own safety as well of that of their customers and the public in general. The lack of previous experience means that apprenticeship is no longer effective, which could put the whole informal sector at risk of being marginalized. Racine Kambwole, the national technical consultant, pointed out that this would eventually alienate the informal sector against the environmentally friendly alternative refrigerants and drive the technicians to recommend traditional solutions to their customers.

The team came up with four recommendations for projects to be further considered in the forthcoming strategy to reduce the consumption of HFCs. Two recommendations focus on developing a training and certification curriculum on good refrigeration practices targeted at technicians in the informal sector, as well the program for this training. With a training curriculum tailored to the needs of the country, it is expected that the efficiency and effectiveness of training initiatives carried out in Burkina Faso would increase. This would consequently lead to an improvement of the practices of technicians in the informal sector and pave the way for an intake of natural refrigerants and further reduction in the consumption of all other refrigerants, particularly HFC-134a (56% of the total importation in 2018) and HFC-410A (27.4% of the total importation in 2018).

The third recommendation is for carrying out an in-depth analysis of the national curricula used in secondary and higher education vocational establishments. Burkina Faso has six different types of degrees for the air conditioning and refrigeration field being taught in eight institutes, and there is a need to ensure that these curricula integrate best knowledge on alternative refrigerants.

The fourth recommendation is for developing a set of guidelines for the installation, testing, maintenance, inspection, safe use, and proper disposal of air conditioning units. The guidelines would also include design and cover handling the lower-GWP refrigerant alternatives and their flammable characteristics. An option is to develop a code of good practices based on identified criteria, which would be useful in streamlining and institutionalizing the sector.

Prof. Dr. Samuel Paré, the Montreal Protocol focal point believes that, with proper funding, the implementation of those four recommendations would enable Burkina Faso to apply the needed training across the entirety of the service sector.

HS Code Expansion: National or Regional?

The question first came up when discussing the Harmonized System (HS) code for tariff nomenclature of the World Customs Organization (WCO) to classify and identify HFC refrigerants and blends more closely for reporting purposes. The present code lumps HFCs and the blends under just two six-digit codes. The code is set to change on January 1, 2022; meanwhile, Parties to the Montreal Protocol are mandated to report their consumption of these refrigerants and need identifiable codes to collect data from their respective customs authorities. The interim recommendation made by UNEP is to expand, at the national level, the six-digit code to eight digits using the extra two digits to differentiate among the different substances. Some Parties had applied this expansion successfully.

The national consultant on customs in Burkina Faso, Souleymane Tou, pointed out the impossibility of doing such an expansion on a national level only, since Burkina Faso is linked to the other ECOWAS countries in a customs agreement and HS codes cannot be altered by any individual member state.

The route through ECOWAS is not an easy one: ECOWAS is made up of countries having three different official languages (English, French, and Portuguese), and communications with their technical and regulatory committees must be in at least two languages and have the support of a few, if not all, members. Moreover, requests by member states are discussed at the pertinent committee meeting which have fixed yearly schedules. Added to this is the complication imposed by COVID-19 by restricting movement and the chance of regional committee meetings where decisions can be made.

Burkina Faso took the lead on initiating contacts with the other ECOWAS countries. The international consultancy provided support with the other francophone member states building on the outcome of a meeting in Guinea Bissau that UNEP had gathered in December 2019 for those countries to discuss this same issue. It became evident that the customs consultant of Benin was the expert on relations with ECOWAS and the team, with the Benin consultant, prepared a draft of a letter petition to the ECOWAS committee for a meeting to explain the background and the requirements for the HS code expansion. The draft had to be approved by the NOUs and customs focal point of all 15 member states, however the pandemic has reduced hopes that the ECOWAS committee will be able to meet to address this issue before the new HS code is in effect on January 1, 2022.

Energy Efficiency Standards & Directives: coherent or conflicting?

For energy efficiency, the integration of national and regional considerations takes a third dimension with both ECOWAS and UEMOA issuing regulation on standards and labels. The team engaged with Bakari Lingani, Energy Engineer at the Directorate General of Energy Efficiency, Ministry of Energy in Burkina Faso, for the information on the national level, and with Charles Diarra, Programme Officer at ECOWAS Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency (ECREEE) located in Cape Verde, to discuss developments at the regional level.

To improve the energy efficiency of electrical equipment, Burkina Faso has implemented an energy control policy through the Ministry of Energy, in particular its Directorate General of Energy Efficiency (DGEE) and the National Energy Agency for Renewables Energies and Energy Efficiency (ANEREE). In 2017, the Ministry of Energy of Burkina Faso issued decree No. 2017-1014 defining the standards and requirements for energy efficiency for appliances and equipment and the modalities of their operation. The decree bans the sale of equipment that does not conform to the minimum energy efficiency levels. Equipment that conforms to the energy efficiency requirements can be imported after acquiring the required authorization from the Minister in charge of Commerce with favorable advice from the Minister in charge of Energy. The decree establishes exceptions for equipment with certain technical use.

The minimum energy performance standards (MEPS) for air conditioners are adopted from the ECOWAS standards referenced ECOSTAND 071-2: 2017, which are issued by ECREEE. On the other hand, the directive on labeling was issued by UEMOA in 2019 and adopted by Burkina Faso in June 2020.

Discussions with the Ministry of Energy have focused on the need to update and streamline the local regulations on energy efficiency in line with the model regulation guidelines issued by United for Efficiency (U4E). The U4E regulation guidelines aim to balance ambitious energy performance and refrigerant requirements while limiting adverse impacts on the upfront costs and of availability of products. “A comprehensive approach includes mandatory, performance-based building energy codes. Neighboring countries should align where practicable to reduce the complexity and cost of compliance for manufacturers, and the challenges of oversight and enforcement for officials. Consistent approaches across countries help yield economies of scale for products that save consumers money on electricity bills, reduce air pollution, mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, and enable greater electrical grid stability.” The team urged Mr. Lingani to take this initiative on a regional level.

Burkina Faso’s Regional Role

In 2018, the Minister in Charge of the Environment accompanied the MP Focal Point Prof. Dr. Samuel Paré to the ASHRAE conference in Las Vegas, Nevada. A meeting with the UNIDO Chief of the Montreal Protocol Division, Mr. Ole Nielsen was arranged in the presence of Mr. Bassam Elassaad of Elassaad & Associates, the international consultancy for Burkina Faso. The minister wanted to discuss the possibility of establishing a regional center of excellence in Burkina Faso for the Francophone African countries to act as an incubator for research and harmonized education. Prof Dr. Paré is in an ideal position to help in the establishment of the center given his position as Vice President of the Thomas Sankara University in Ouagadougou, which is a candidate host for the center. U4E helped establish a similar center for Anglophone Africa at the University of Rwanda and can play a similar role for Burkina Faso.

Lessons Learned

The work on the enabling activities has consolidated the close cooperation of the Burkina team during adverse situations imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Adama Sawadogo, Deputy National Ozone Officer for Burkina Faso attributes this to the high sense of responsibility and ethics of the team added to the clear objectives of the enabling activities, which set reasonable and achievable goals.

The first lesson learned is that for any program to work, stakeholders in the whole sector must be informed, trained, and kept involved. This means that the informal service sector can no longer be ignored, and training must be harmonized and streamlined. Incidentally, the work done by RAC sectors associations in Burkina Faso, i.e. AITFB, Association of Refrigeration Engineers and Technicians of Burkina Faso and APFC, Association of Professionals in Refrigeration and Air Conditioning, and U-3ARC, the newly founded Union of Associations of African Actors in Refrigeration and Air Conditioning, which is based in Burkina Faso, will contribute to the formalization of the informal sector through the organization of free workshops and the awareness campaigns in the country.

The other lesson learned is that regional cooperation has become indispensable: programs and initiatives launched on a regional scale are far more effective rather than being repeated inefficiently across neighboring countries.

“Working with the Burkina team has been an invigorating experience; I am amazed by their energy and enthusiasm”, said Sonja Wagner, member of the international consultancy team. “Burkina Faso might have a limited consumption, but its experience will echo large and far across the whole African continent”, said Guillaume Cazor, UNIDO Project Associate for the Enabling Activities project in Burkina Faso.

“One big lesson this project has re-emphasized, is the importance of matching international expertise with local expertise and knowledge of the terrain”, said Ozunimi Iti, who manages the Enabling Activities project in Burkina Faso. “The combined teams of UNIDO and the Burkina Faso National Ozone Unit, were able to not only identify and propose solutions to local bottlenecks such as the dangers of new refrigerants within the apprenticeship system but also to create momentum to solve a problem with regional implications, where until now, only national solutions had been proposed.”

CONTACT US

Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to receive a quarterly email with updates and new content!

Disclaimer

The information presented in this newsletter does not necessarily reflect the views of UNIDO. Links to external websites are included solely to provide additional information and do not imply any official endorsement of the opinions, ideas, data, or products presented.

© 2020 UNIDO Montreal Protocol