Share this:

Welcome to the UNIDO Montreal Protocol Newsletter

This issue invites you to learn more about global initiatives to preserve the ozone layer and fight climate change, inspired by this year’s theme for the International Day for the Preservation of the Ozone Layer: “Global Cooperation Protecting Life on Earth.”

Our feature article “UNIDO, UNEP and WHO celebrate the International Day of Clean Air for blue skies 2022” highlights the importance of partnerships for driving action on environmental protection. A major sign of progress in this field recently came from the global scientific community, announcing that the hole in the ozone layer could be healed by the year 2070.

At UNIDO, we are committed to driving further action on ozone layer protection, while finding synergetic approaches to tackle other climate goals. For a real world example, our interview with the National Ozone Unit of Oman outlines Oman’s efforts to identify technologies with lower global warming potential and opportunities for low-carbon transportation development.

Our Ask UNIDO segment “The crux of implementing climate-friendly and sustainable cold chain policies” discloses concrete measures to promote the use of environmentally sound cold chains. From the combined perspective of UNIDO’s Project Coordinator and the National Policy and Regulations Coordinator in the field, this article provides useful insights into policymaking, with positive examples from across the globe.

For answers to your own pressing questions, please submit your queries via the form at the bottom of the page, which we will gladly answer in the “Ask UNIDO” section of the next issue.

Happy reading!

Your UNIDO Montreal Protocol Unit Team

ASK UNIDO

Mae Valdez | Franziska Menten

Debating the challenges of policies and regulations for the food cold chain and showing some of the best practice around the globe when it comes to integrating energy efficiency and low-GWP solutions into national policy, standards and regulations.

INTERVIEW

Khamis Mohamed Alzeedi

On Oman's achievements under the Montreal Protocol, ambitions under the Kigali Amendment and proposed strategy on a low-carbon transportation development.

FEATURE ARTICLE

Keira Ives-Keeler

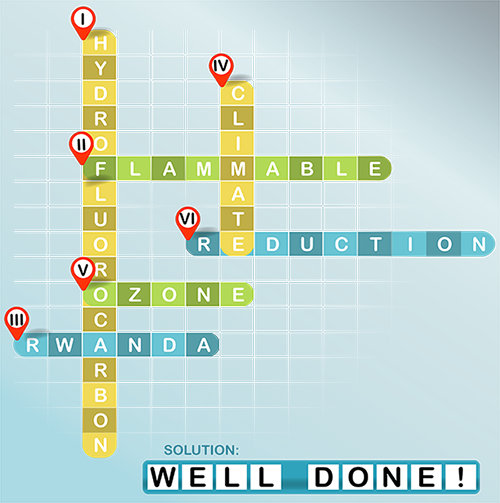

QUIZ - Did you know?

Test your knowledge!

UNIDO's Montreal Protocol Unit's implemented projects in 2021 potentially avoided how many tons of CO₂ emissions

146 countries have already ratified the Kigali Amendment. How many ratified this year in 2022?

Belarus, Brazil, Congo, Indonesia, Italy, Mongolia, Morocco, Nauru, Philippines, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Singapore, Solomon Islands, Tajikistan, United Republic of Tanzania, United States of America, Venezuela, Zimbabwe

Do you know that sustainable cooling exist already for more ………….?

NOTICE BOARD

Spotlight

Check out the Philippines Cold Chain Innovation Hub, displaying innovative best-in-class systems and components for sustainable cold chain applications from contributors around the globe.

Social Media

Travel with us to Tierra del Fuego, where UNIDO together with the National Ozone Unit of Argentina, carried out a field visit to the air-conditioning (AC) manufacturing hub of the country.

Events

Follow us to the jointly organized side event that took place at the 34th MOP and learn about existing and new training tools on handling flammable refrigerants.

ASK UNIDO

You Ask, We Answer!

Mae Valdez, National Policy and Regulations Coordinator for UNIDO in the Philippines and Franziska Menten, Project Coordinator at UNIDO, debating the challenges of policies and regulations for the food cold chain and showing some of the best practice around the globe when it comes to integrating energy efficiency and low-GWP solutions into national policy, standards and regulations.

(7 minutes reading time)

ASK UNIDO: The crux of climate-friendly and sustainable cold chain policies

Setting the scene: Complexity and impact of food cold chains

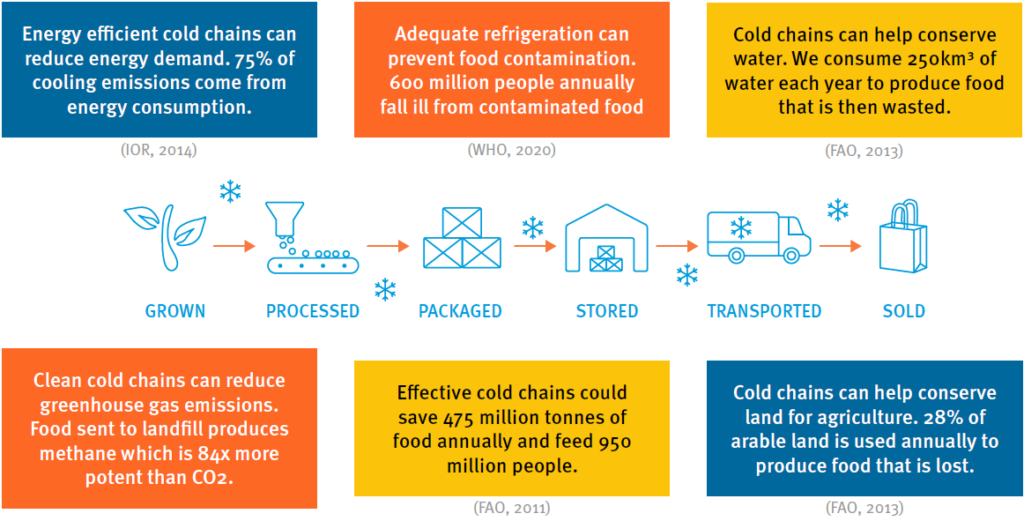

Access to cold chains plays a significant role in inclusive and sustainable industrial development by prolonging the shelf life of agriculture produce from rural areas and linking them to a wider market, thereby, increasing the income of farmers and raising their quality of life. Aside from preventing food spoilage and losses, it also ensures the availability of buffer stocks in times of crisis or disasters in the country.

In agriculture, lack of refrigeration has compounding negative effects. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that one third of all the food produced worldwide are lost and wasted[1], and this is greater among smallholder farmers in Africa and Asia where cold chain infrastructure is inadequate or non-existent. Cold chain refers to the food supply logistics chain that uses refrigeration technology to continuously maintain a suitable temperature and humid environment for perishable products such as fruits, vegetables, dairy, meat, and fish[2]. Thus, it is a system starting at post-harvest up until display at retail stores which includes pre-cooling, refrigerated transport, cold storage, food retail and food services.

Source: “Montreal Protocol and beyond: 17 stories along the journey from ozone layer protection to sustainable development”: https://indd.adobe.com/view/650c7261-7cb3-4a30-85ed-383c633240f7

Conversely, traditional cold chains are a substantial and growing contributor to climate change due to hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) refrigerants used with their high Global Warming Potential (GWP), as well as the high energy consumption during the cold chain cycle.

Developing climate-friendly and sustainable cold chains not only prevents emissions at source, but also the emissions attributable to food loss and waste. The lack of adequate cold chains is responsible for about 9% of lost production of perishable foods in developed countries and 23% in developing countries.

Challenges for regulating the food cold chain

Cold chains span nations, regions and global trade routes. Given their complexity, there is no single law or government agency mandated to develop and regulate the cold chain market. Policies often pertain to the components, purpose and location of the cold chain infrastructure, but not for the whole process. Since it is often used for agriculture products, accreditation of cold storage facilities are mostly done by the Ministry related to Agriculture through its attached bureaus and agencies. In terms of harmful substances and energy performance used in its operations, depending on the country, the ministries of Environment, Energy, Trade and Standards have usually respective regulations according to their agency’s function. This shows that inter-agency collaboration is crucial for creating an enabling policy environment for sustainable and climate-friendly cold chains.

Aside from tedious requirements, cold chain regulators have not been able to adopt actions to cut down its emissions. As an industry that produces high levels of GHG through its energy intensive operations and refrigerant use prone to leakage without proper disposal, a comprehensive and unified policy environment addressing these issues should be implemented by all regulatory agencies concerned.

Collectively, three international agreements – the Paris Agreement; the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; and the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol- provide the foundation of inclusive and climate-friendly cold chains, creating a direct intersect between internationally agreed goals for the first time.

Improving access to energy-efficient and climate-friendly refrigeration through enhanced cold chains would deliver more economic, environmental, and health benefits through reduced food loss and waste. This would also contribute to addressing social inequality by linking the rural food producers to a wider market and increasing their income and quality of life. Furthermore, this would also support global health campaigns, as recently seen with the vaccination rollout needed to address the Covid-19 pandemic.

Cold chains, including commercial, industrial and mobile refrigeration systems, are among the most energy intensive sectors worldwide. According to a study[3] 35%–45% of the total electricity consumption of a typical supermarket is used for refrigeration, and around 70% of this refrigeration energy is used to store and display frozen and chilled food products at suitable temperatures[4]. This empathizes the importance of energy efficient refrigeration systems in cold chain combined with low-GWP refrigerants in driving down emissions from this growing sector.

Source: “Montreal Protocol and beyond: 17 stories along the journey from ozone layer protection to sustainable development”: https://indd.adobe.com/view/650c7261-7cb3-4a30-85ed-383c633240f7

Policy instruments reducing CO2 emissions in the cold chain

Energy efficiency in cold chains should therefore be addressed using a holistic approach to maximize all energy savings opportunities, reduce costs for end users, and to reduce environmental impacts.

Some examples of general policy instruments using a more integrated and holistic approach are as follows:

- Policies supporting the shift to low-GWP refrigerants such as natural refrigerants (e.g. CO2, ammonia and hydrocarbons)

- Update of standards for low-GWP refrigerants to align with the anticipated phasedown of HFCs and with the available technology in the market (e.g. IEC 60335-2-89)

- Development/update of minimum energy performance standards (MEPS) for the cold chain industry; use of renewable energy sources

- Development/update minimum energy efficiency performance for products (MEPP)

- Better energy management related to smart grid technologies

- Adoption and enforcement of policies aiming to reduce refrigerant emissions through ban on venting and other measures

- Inclusion of environmental management aspect (e.g. disposal/capture/recycling of refrigerants)

- Exploring synergies with national climate change action plan, nationally determined contribution (NDC) targets, national cooling plan

International benchmarks: examples from the US, India and the Philippines

Many countries have initiated policy measures to enable the entry of low-GWP refrigerants into the market as a step to phase down HFCs and make cold chains more sustainable. This could serve as a reference for other countries that aim to prepare for the shift to low-GWP refrigerants in light of the Kigali Amendment’s scheduled phase-down of HFCs. Just a few selected examples are listed below.

USA

The United States’ Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) implements the Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP) by virtue of Section 612 of its Clean Air Act. It seeks to identify and evaluate substitutes for ozone-depleting substances (ODS) by assessing the overall risks to human health and the environment of existing and new substitutes. It also publishes lists, promotes the use of acceptable substances, and provides the public with information regarding acceptable substitutes.

Due to its flammability and safety issues, adoption of low-GWP refrigerants is restricted by current policies. However, the SNAP sets a good example for a policy measure that enables the adoption of low-GWP refrigerant systems at par with the speed of ongoing innovations and new technologies.

India

India’s strategy presents a more holistic approach reflected in their national cooling plan which serves as a blueprint for the sustainable transition of all their cooling sectors. The directions stated in the plan are grouped as short-, medium- and long-term recommendations which would shape government priorities. For the cold chain sector, these include the following:

- Link the incentives being provided for development of cold-chain infrastructure with adoption of energy-efficient design, construction and maintenance practices and low-GWP refrigerant and renewable technologies

- Develop Management Information System through inter-ministerial collaboration, to track relevant information on infrastructure development and e-performance monitoring to improve overall efficiency of the cold-chain system.

- Develop safety standards for flammable and toxic refrigerants for cold storage and other segments of the cold chain

- Provide capacity building for technicians with national level certification schemes. Training should cover aspects such as installation and maintenance of refrigeration plant, energy efficient operation, and safe installation, management and recycling of equipment and refrigerant.

The most important element of India’s national cooling plan pertaining to cold chains is the intent to link the incentives for energy efficient design and low-GWP refrigerant technology.

Philippines

In the Philippines, there are incentives provided for energy efficiency but linking that with low-GWP refrigerant technology is yet to be realized. The Philippines is one step ahead in the development of a management information systems. This initiative is envisions B2B functions for cold storage operators and users, as well as monitoring functions for planning, investment programming and policy making for cold chain regulatory agencies. Furthermore, the Philippines has already published standards for low-GWP refrigerants (IEC 60335-2-89 version 3.0). Once published, regulatory agencies may conduct a review of their respective cold chain accreditation process and incorporate the updates within their respective administrative guidelines and requirements. The country’s Energy Efficiency and Conservation Law (Republic Act 11285) provides a regulatory framework for minimum energy performance for various stages within the cold chain. It also mandates high energy consuming cold storage warehouses to develop and implement an energy management system in their operations. The Cold Chain Industry Roadmap implemented by the National Cold Chain Committee, an inter-agency and multi-sectoral body, creates other opportunities for synergy on cold chain regulation. Its action agenda includes strategies to ensure reliable energy through the use of renewables and energy efficient measures.

[1] http://www.fao.org/platform-food-loss-waste/en/

[2] Mercier, et. Al., 2017

[3] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306261916310285?via%3Dihub

[4] Alzuwaid et al., 2016

INTERVIEW

Interview with Khamis Mohamed Alzeedi

National Ozone Officer of Oman, on Oman's achievements under the Montreal Protocol, ambitions under the Kigali Amendment and proposed strategy on a low-carbon transportation development.

(4 minutes reading time)

- Can you tell us a little bit about your background, how you started to work in the sector and your experience as the National Ozone Officer for Oman?

Because of my interest to work in the field of environment, I joined Air and Noise Pollution Control Section in the Ministry of Environment in 1992. I started to work as an Air and Noise Pollution Inspector, eventually becoming Head of the same section. After that, I was promoted to the position of Deputy Director of the Environmental Inspection and Control Department. In 2008, I was promoted to the Director of Climate Change Control Department, then Director of Climate Mitigation.

I started working as a National Ozone Officer in 2001 and the experience since that time until now has been a very enjoyable one that enabled me to understand and appreciate the importance of contributing to the protection of the ozone layer, because of its importance in protecting the planet and life on Earth.

I really feel proud to be part of the success story of the Sultanate of Oman in the field of ozone layer protection during these years. The most important milestones that I was part of, were the establishment of a special division for the protection of the ozone layer, development of the necessary legislation and its development over time, as well as the development of the national e-licensing system.

Perhaps, the most important of these achievements is the Sultanate of Oman’s ability to fulfill its obligations towards the Montreal Protocol ever since its ratification in 1998.

- What are the priority sectors and targeted activities in Oman’s HCFC Phase-Out Management Plan?

Since Oman is classified as a country with extremely hot weather[1] especially in summer, the priority sector is the refrigeration and air conditioning sector. Where the majority of HCFCs refrigerants are used in the RAC servicing sector.

The targeted activities in the HCFC phase out management plan for Oman include the following:

- Training of about 1000 technicians in the RAC sector on the best practices during servicing activities.

- Development of a certification system for the servicing technicians.

- Establishment of five reclamation, recovery and recycling centers to help the Sultanate of Oman in achieving the targeted plan to phase out HCFCs and to ensure the availability of these gases after the phase out stage.

- Supply 5 training institutes with training equipment and materials required for training and certification purposes.

- Development of specifications for newly emerging technologies and substances such as safety standards for using hydrocarbons.

- Organize activities related to public awareness for different sectors (public, private and government sectors) on the importance of protecting the ozone layer and new technologies that are both ozone and climate friendly.

- What is Oman’s experience in identifying alternative solutions for High Ambient Temperature (HAT) countries?

In Oman, most of the buildings are designed to achieve the maximum cooling efficiency.

The country has also adopted specifications for refrigeration and air conditioning equipment for optimal energy efficiency.

Nowadays, the relevant organizations are also working on the update of the building codes to maximize the energy and cooling efficiency.

- Which challenges will Oman be facing in the next years, implementing the Montreal Protocol and Kigali Amendment? What are some particular synergies which can be noted with the Paris Agreement?

The biggest challenge will be finding the best technologies and alternatives that are suitable for Oman’s hot weather and at the same time are commercially feasible.

Another challenge is to find new alternatives with low global warming potential (GWP) which is essential to Oman to implement its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that are submitted under the Paris Agreement.

- What are the key lessons from implementing the HPMPs in Oman which other NOUs could benefit from?

The key lessons learned from the implementation of the different stages of HPMPs in Oman are:

- The importance of identifying the key sectors that depend on the use of HCFCs to establish the best transition and phase-out requirements.

- Early preparation and adoption of new regulations, specifications and standards for new alternatives and technologies are also essential for smooth transition.

- Training of technicians dealing with refrigerants on best practices is key factor for the success of any phase-out plan.

- Oman has recently partnered with UNIDO to work on a low-carbon transportation development strategy project with funding from the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which was approved in July. Congratulations! Can you tell us about the overarching goal of the project and the importance of this project for Oman?

Through a quick analysis of the transport sector in the Sultanate of Oman, the following can be concluded in terms of the importance of this project for Oman:

The most challenging sector to decarbonize in the sultanate of Oman is the transportation sector, which contributed over 14% of Oman’s total carbon emissions in 2015.

The transportation sector in the Sultanate of Oman will have difficulty meeting any reduction goals due to the continued reliance on fossil fuels, with negligible use of clean energy.

The total demand for transport in Oman will increase, and society will emphasize punctuality, personalization, and comfort. This will make managing total carbon emissions and transportation’s carbon intensity more difficult.

Due to the importance of transportation to Oman’s economic and social development, reducing emissions is essential for the country’s long-term decarbonization strategies.

[1] Oman is a so called High Ambient Temperature (HAT) country Parties to the Montreal Protocol recognized in 2009 about the non-availability of low-GWP refrigerant options for HAT

FEATURE ARTICLE

UNIDO, UNEP and WHO celebrate the International Day of Clean Air for blue skies 2022

Keira Ives-Keeler, Editor and Media Specialist at UNIDO, on the importance of celebrating the International Day of Clean Air for blue skies.

(3 minutes reading time)

UNIDO, UNEP and WHO celebrate the International Day of Clean Air for blue skies 2022

The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) partnered with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Health Organization (WHO) to celebrate this year’s International Day of Clean Air for blue skies. The theme for this year’s day is The Air We Share to focus on the transboundary nature of air pollution that requires collective accountability and global, regional and local cooperation.

Air pollution does not have boundaries; it is intrinsically a transboundary problem. Depending on the local or regional atmospheric conditions, any mass of polluted air produced indoors or outdoors can be carried by wind, moving from one place to another, crossing local, national, regional and even transcontinental boundaries. Mobile emitting sources like ships and planes pollute the air with exhaust gases. Through global distillation, known also as the “grasshopper effect,” persistent organic pollutants (POPs) like DDT are transported from the tropics and warmer places to the North and South Poles, and colder places. Pollutants like mercury can evaporate and attach to airborne particles until it is removed by gravitational force or elements such as rain, snow, or fog.

In 1974, scientists Mario Molina, Sherwood Rowland and Paul Crutzen discovered that the ozone layer was being depleted through the use of common household chemicals like refrigerants and spray can gases; they won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995. This great discovery led to the adoption of the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer on 16 September 1987, which has served as a reference for other multilateral environmental agreements like the Stockholm Convention on POPs and the Minamata Convention on Mercury.

For this reason, and aligned to the topic “We care about the right to clean air: UN work on industry, environment and health” the three UN agencies came together to share perspectives on industry approaches to meeting air quality standards, as well as ways to contribute to cleaner air that protects health and the environment. Any single effort to deal with indoor and outdoor air pollution locally adds to those made by others and can result in positive impacts globally.

With the support of a number of funding partners, including the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Global Climate Fund (GCF) and the European Union (EU), UNIDO supports Member States in the implementation of multilateral environmental agreements related to the reduction or elimination of emissions of toxic air pollutants.

Through its work on the Minamata Convention, UNIDO is helping to reduce mercury use in the artisanal and small-scale gold mining sector by installing mercury-free processing plants in Burkina Faso, Mongolia and the Philippines. These projects are funded by the GEF under the planetGOLD programme. In the past two years UNIDO has also reduced or phased out over 7,500 metric tons of pollutants through its work related to the Stockholm Convention on POPs, also with support from GEF. UNIDO interventions in support of the Montreal Protocol have led to the phasing out of almost 80,000 metric tons of ozone depleting substances in over 90 countries since 2010.

As air pollution contributes to climate change and causes significant damage to human health and our natural environment, actions in this area can reap multiple benefits across industrial sectors from the fashion industry to construction.

Written by Keira Ives-Keleler, UNIDO Editor and Media Specialist at Responsible Materials and Chemicals Management Unit

See original published article on our UNIDO website: https://www.unido.org/news/unido-unep-and-who-celebrate-international-day-clean-air-blue-skies-2022

CONTACT US

Subscribe to our newsletter

Sign up to receive a quarterly email with updates and new content!

Disclaimer

The information presented in this newsletter does not necessarily reflect the views of UNIDO. Links to external websites are included solely to provide additional information and do not imply any official endorsement of the opinions, ideas, data, or products presented.

© 2022 UNIDO Montreal Protocol